Wonderland Burlesque's

Let's All Go To The Movies

She's A Lady!

Part XLIX

Yes, sometimes? It takes a lady.

And sometimes? That lady is more than fair... she's a visual delight!

Or so this film would have us believe.

It promises lots of (behind the scenes) drama, a bit of comedy, a dash of music, and a lot of dirt!

Let's take a walk down Hollywood Blvd. and shine a light on this magnificent classic film.

This way, if you please. But remember...

Ladies first!

--- ---

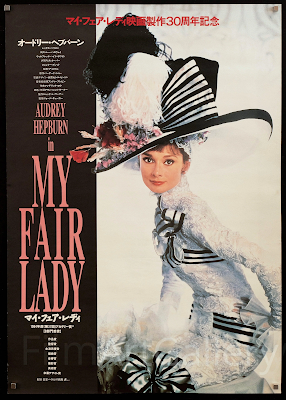

(1964)

Pompous phonetics Professor Henry Higgins is so sure of his abilities that he takes it upon himself to transform a Cockney working-class girl into someone who can pass for a cultured member of high society. His subject turns out to be the lovely Eliza Doolittle, who agrees to speech lessons to improve her job prospects. Higgins and Eliza clash, then form an unlikely bond, one that is threatened by aristocratic suitor Freddy Eynsford-Hill.

This American musical comedy-drama was adapted from the 1956 Lerner and Loewe stage musical based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 stage play Pygmalion. With a screenplay by Alan Jay Lerner and directed by George Cukor, it stars Audrey Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle (replacing Julie Andrews from the stage musical) and Rex Harrison as Henry Higgins (reprising his role from the stage musical) with Stanley Holloway, Gladys Cooper and Wilfrid Hyde-White.

CBS head William S. Paley made an arrangement where CBS would finance the original Broadway production in exchange for the rights to the cast album (through Columbia Records). Warner Bros. then purchased the film rights from CBS in February 1962 for the then-unprecedented sum of $5.5 million plus 47¼% of the gross over $20 million. Paley added a condition to the Warner contract that ownership of the film negative would revert to CBS seven years following release.

Jack L. Warner wasn't keen on the idea of Rex Harrison reprising his stage role. Peter O'Toole, Cary Grant, Noël Coward, Rock Hudson, Michael Redgrave, and George Sanders were all under consideration for the role. Warner wanted Cary Grant. He was also in negotiations with Peter O'Toole, extremely hot after his Lawrence of Arabia (1962) success, but O'Toole's agents were looking for $400,000, while Harrison was only asking for $200,000.

When asked why he turned down the role of Professor Henry Higgins, Cary Grant remarked that his original manner of speaking was much closer to Eliza Doolittle's. He also told producer Jack L. Warner that not only would he not play Professor Henry Higgins, but if Rex Harrison was not cast in the role, he wouldn't even go see the movie.

After screening the rough cut, producer Jack L. Warner, who had not wanted to cast Rex Harrison, rose in silence, turned to the actor, and bowed.

James Cagney was originally offered the role of Alfred P. Doolittle. When he pulled out at the last minute, it went to the man who played it on Broadway, Stanley Holloway.

Audrey Hepburn was guaranteed $1 Million. She revealed many years later that had she turned down the role of Eliza, the next actress to be offered it would not have been Julie Andrews, but Elizabeth Taylor, who wanted it desperately. Jack L. Warner's was also considering Shirley Jones. Meanwhile, Shirley MacLaine and Connie Stevens were both campaigning for the role.

Audrey Hepburn believed that Julie Andrews should have played Eliza Doolittle in this movie. Andrews said that she "threw a few tantrums" when she learned that she wouldn't be playing Eliza in this movie, and yet she got along very well with Hepburn without holding a grudge against her as she knew Hepburn was an innocent party in the whole thing. Andrews would instead appear in Walt Disney's Mary Poppins that same year, for which she won the Oscar for Best Actress for her role as the titular character. The controversy over Hepburn being cast over Andrews went as far as journalists claiming there was a feud between the two actresses. This, of course, was untrue, as Hepburn and Andrews were friends in real life and had great respect for one another.

Audrey Hepburn had signed for the movie with the understanding that she would do her own singing. She arrived in Hollywood six weeks before shooting began to work with a vocal coach and musical director André Previn and actually recorded her tracks for the musical numbers. When Hepburn was first informed that her voice wasn't strong enough and that she would have to be dubbed, she walked out. She returned the next day and, in a typically graceful Hepburn gesture, apologized to everybody for her "wicked behavior." Hepburn later admitted she would never have accepted the role of Eliza Doolittle if she had known that producer Jack L. Warner intended to have nearly all of her singing dubbed. After making this movie, Hepburn resolved not to appear in another movie musical unless she could do the singing on her own.

Most of Audrey Hepburn's singing was dubbed by Marni Nixon (but not all). This was primarily due to the songs not being transposed down to a key appropriate for Hepburn's voice. Hepburn sang most of Just You Wait, as well as the reprise to the song, showcasing her ability to sing perfectly at ease when the songs were set in a reasonable key.

Hepburn was not the only one dubbed. Jeremy Brett was very surprised to learn that all of his singing was to be dubbed by a 43-year-old American named Bill Shirley, especially since his own singing voice at that time was remarkably good. Apparently it was because he was a baritone and they wanted a tenor.

Audrey Hepburn announced the assassination of John F. Kennedy to the devastated cast and crew on November 22, 1963, immediately after filming Wouldn't It Be Loverly? on the Covent Garden set.

At Audrey Hepburn's insistence, director George Cukor shot all of her scenes in sequence so that she could grow into the role and hold her own against Rex Harrison and Stanley Holloway, who had both done the play for several years. It also allowed her to do the most difficult scenes first, those before Eliza's transformation, while she was still fresh. The shoot was unusually exhausting for Audrey Hepburn, who lost eight pounds during filming. Her work was intensified by domestic problems with husband Mel Ferrer, who was playing a supporting role in Sex and the Single Girl (1964) on the Warner Brothers' lot. Things became so bad that Cukor had to shoot around her for a week so she could get her health back.

Audrey Hepburn's failure to win an Oscar nomination was considered a major upset, triggering protests from Warner Brothers and director George Cukor. She rose above the snub, however, when the Academy invited her to present the Best Actor award, which went to co-star Sir Rex Harrison.

Rex Harrison was very disappointed when Audrey Hepburn was cast as Eliza Doolittle, as he felt she was badly miscast, and he had hoped to work with Julie Andrews. He told an interviewer, "Eliza Doolittle is supposed to be ill at ease in European ballrooms. Bloody Audrey has never spent a day in her life out of European ballrooms." Nevertheless, Harrison was once later asked to identify his favorite leading lady. Without hesitation, he replied, "Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady (1964)." However, it was widely believed he made this remark because he knew her fans wanted him to say that.

The song I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face held special memories for the actor, as during the original Broadway run he used to sing the song to his third wife Kay Kendall, who would stand in the wings watching his performance. Harrison later admitted that when he sang the song in this movie, he was thinking all the time about Kendall, who had died a few years before from leukemia. When Harrison accepted his Academy Award for this movie, he dedicated it to his "two fair ladies," Audrey Hepburn and Julie Andrews.

Despite extensive vocal training after landing the part of Professor Henry Higgins in this movie, Rex Harrison was unable to sing a note. In the end, director George Cukor gave up and told him to quasi-speak the whole thing as he had done in the stage version. Because of the way Harrison talked his way through the musical numbers, they were unable to pre-record them and have him lip-sync, so a wireless microphone (one of the first ever developed) was rigged up and hidden under his tie. However, this meant that his mouth and words were completely in sync and everyone else's looked off, since they were lip-synching (when everyone is lip-synching, it's not that noticeable). The studio thought that this was too obvious so they altered Harrison's soundtrack, lengthening and shortening notes in various places so that his synchronicity is slightly off like all of the other actors and actresses.

Joshua Logan wrote in his autobiography that he was offered the chance to direct this movie, but the offer was withdrawn when he suggested that some scenes be shot on-location in London. The original choice to direct this movie was Vincente Minnelli, but when his salary demands were too high, the job went to George Cukor.

Director George Cukor and costume/production designer Cecil Beaton, who were good friends beforehand, had a big falling-out during the production. Cukor complained that Beaton tried to take credit for other people's work. He also resented the fact that Beaton's presence prevented him from hiring his usual color consultant, photographer George Hoyningen-Huene. For his part, Beaton considered Cukor vulgar and resented his domineering character. Some observers suggested that the closeted Cukor was put off by Beaton's more flamboyant homosexuality. There were even rumors that Beaton had once stolen a man from Cukor.

Cukor and Beaton's biggest on-set argument was over Beaton's assignment to photograph the cast. Cukor felt that his photography was slowing down production and told him to stop taking shots on the set. Then he complained that posing for the portraits was overworking the actors and actresses. Yet Beaton persisted in taking pictures. After some on-set blow-ups, Cukor complained to Warner Brothers, and Beaton stopped coming to the set. Beaton also had a habit of setting up his art easel to sketch and paint the sets while filming was in progress. Producer Warner and Cukor had Beaton banned from the daily filming stage, as well as from any Warner Brothers stage on which set construction, painting, set green, and set decorating was in progress.

Costume designer Cecil Beaton created 1,500 costumes for this movie, with the exception of the pearl white gown Hepburn wears to the Embassy Ball, an original Edwardian specimen Beaton found in an antique shop. When Hepburn entered the set for the first time in Eliza's gown for the ball, she was so beautiful the crew and the rest of the cast stood silently gaping at her, then broke out with applause and cheers. For the early part of Eliza's transformation, Beaton insisted that Hepburn wear weights around her lower legs so that she would keep some of the flower girl's early gawkiness. Most costumers and make-up artists had to camouflage Hepburn's square jaw, but for her early scenes, production designer Beaton actually emphasized it by putting her in a straw hat. That allowed for a more dramatic transformation, accentuated by the upswept hairdos he designed for her later in the movie to show off her bone structure. All hats were created by Parisian milliner Madame Paulette at Beaton's request.

Cukor and Cecil Beaton took a lavish approach to this movie's set design. In a departure from standard Hollywood practice, rather than building cobblestones for the Covent Garden streets from a single mold, they had each stone made individually. Art director Gene Allen, a frequent Cukor collaborator, used several coats of paint on the buildings to create the illusion that they were hundreds of years old. Production designer Gene Allen went on record to say that Beaton only designed the women's clothes and had no part in the actual designs of the sets, though he insisted on taking the credit for them. In fact, Beaton had it written into his contract that he receive sole credit for production designer. Allen was never given a budget with which to work. He just designed and had built all of the sets without having to worry about how much they cost. When director George Cukor asked to do expensive retakes of the Ascot sequence, Warner Brothers refused. When Cukor persisted, the company had the set torn down. At $17 million, this was the most expensive Warner Brothers movie produced at the time. Nevertheless, it went on to become one of the biggest grossing movies of 1964.

A critical and commercial success, it became the second highest-grossing film of 1964.Nominated for twelve, it won eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor.

--- ---

And that's all for now, folks...

And that's all for She's A Lady!

Tune in next time...

Same place, same channel.

---- ----

My Fair Lady - Movie Trailer

(1964)

.webp)

2 comments:

As far as classic Hollywood musicals go, that one of pretty good.

My Fair Lady und Gigi waren in den 1960er Jahren die erfolgreichsten Filme a den Kinokassen in der DDR und Osteuropa.

Eskapistische Filme, die das Leben besser machten.

(vvs)

Post a Comment